Atlantis: The Most Elusive Island in History

Randomly place your finger on a map, and chances are I could find you an interpretation of Plato's Dialogues asserting that Atlantis is precisely where your finger lands.

The array of locations attributed to Atlantis throughout history is staggering. From Africa, Spain, the Caribbean, Bolivia, Antarctica, to the Atlantic... Many brilliant minds have scrutinized Atlantis, formulating theories about its whereabouts and staunchly affirming the existence of this lost Eden where human culture once peaked, fell, and has yet to reclaim.

But where is the true location of Atlantis?

Plato's ideal.

The first accounts of Atlantis appear in Plato's Socratic dialogue in two parts: Timaeus and Critias (360BC).

At the beginning of Timaeus, Plato mentions Atlantis for the first time: "Then listen, Socrates, to a tale which, though strange, is certainly true, having been attested by Solon... For these histories tell of a mighty power... This power came forth out of the Atlantic Ocean, for in those days the Atlantic was navigable; and there was an island situated in front of the straits which are by you called the Pillars of Heracles; the island was larger than Libya and Asia put together... Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent, and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia..... But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea."

In Critias, Plato goes into greater detail about Atlantis' geography and wealth: "...they had such an amount of wealth as was never before possessed by kings and potentates, and is not likely ever to be again... For because of the greatness of their empire many things were brought to them from foreign countries, and the island itself provided most of what was required by them for the uses of life. In the first place, they dug out of the earth whatever was to be found there, solid as well as fusile... orichalcum was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island, being more precious in those days than anything except gold. There was an abundance of wood... there were a great number of elephants... there was provision for all other sorts of animals... Also whatever fragrant things there now are in the earth, whether roots, or herbage, or woods, or essences which distill from fruit and flower, grew and thrived in that land; also the fruit.. we call them all by the common name pulse, and the fruits having a hard rind, affording drinks and meats and ointments, and good store of chestnuts and the like... that sacred island... brought forth fair and wondrous and in infinite abundance. With such blessings the earth freely furnished them..."

Atlantis: Not a Tale, but a True Story

The story of Atlantis is not a mere tale; it is a true story.

Plato faced no critique from his contemporaries regarding the tale of Atlantis. In fact, Aristotle, Plato's own student, never dismissed Plato's Atlantis as mere fiction. On the contrary, Thorwald C. Franke argues that Aristotle "expresses support for many relevant details, suggesting he is far from denying the existence of Plato's Atlantis."

Other eminent philosophers also accepted the tale of Atlantis as historical fact.

H.S. Bellamy discovered over 100 references to Atlantis in post-Platonic classical literature.

Plato's account of Atlantis has stood the test of time.

While discussion of Atlantis waned after the 6th century, two events in the 15th century reignited interest in this enigmatic land.

The first was Marsilio Ficino's translation of Plato’s work into Latin, and the second was Christopher Columbus' discovery of the New World. Suddenly, people grasped that the world was far larger than they had previously thought, and Atlantis held the promise of boundless riches awaiting discovery. Who wouldn't dream of finding paradise?

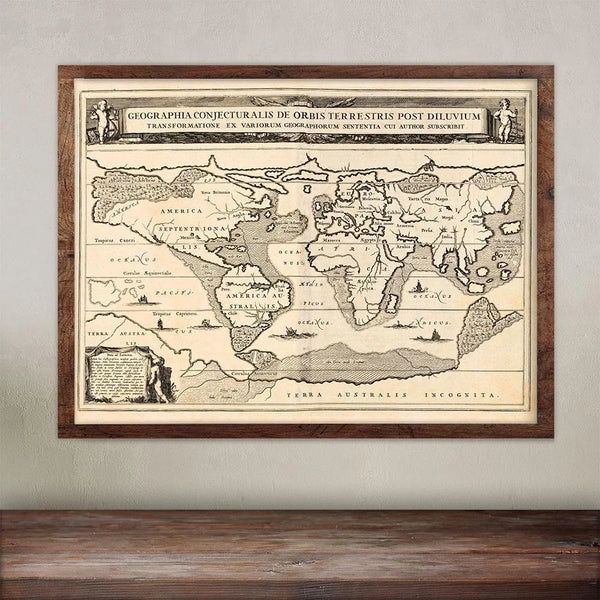

The earliest known map of Atlantis came from a German Jesuit in 17th-century Rome: Athanasius Kircher. A man of intense piety, he was also a polymath and prolific author. Kircher proposed a theory likening the Earth to a living body, with water flowing in and out. Placing Atlantis on his map was primarily to bolster his theory.

Atlantis began to take on a more tangible form.

Map from 1675, Amsterdam, by Athanasius Kircher showing Atlantis between Spain and America, with enlargement of Atlantis' location.

Bory de St Vincent, an erudite French politician and naturalist, posited Atlantis as the cradle of all civilization.

In his work "Essais sur les isles fortunées," he hypothesized that Atlantis had undergone two cataclysmic events. The first was a volcanic eruption in the Mediterranean that halved the island. The second occurred after the Atlanteans' defeat by the Athenians, causing the remaining portion of Atlantis to sink, leaving only the remnants we now know as the Canary Islands, Madeira, and the Azores.

Bory de St Vincent may have drawn inspiration from J.P de Tournefort, who, a century earlier, suggested that a Mediterranean earthquake had unleashed a surge of water that inundated Atlantis.

To bolster his argument, Bory de St Vincent created an illustrative map titled "Carte conjecturale de l'Atlantide."

The fascination with Atlantis was reinvigorated with fervor by American Congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly when he released his immensely popular book "Atlantis: The Antediluvian World" in 1882.

Donnelly took Plato's myth and expanded upon it, adding embellishments and forging new connections between the Atlanteans and the Mayans. In essence, he shaped the grand Atlantis as we envision it today.

Donnelly didn't contest Plato's proposed location for Atlantis. In his book, we encounter a map that places Atlantis precisely where it is described in Timaeus.

In 1885, William F. Warren, President of Boston University, penned a book titled "Paradise Found: The Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole" (1885), proposing the North Pole as the location of Atlantis and the birthplace of humanity.

Since no one had ventured there at the time, Warren's conjectures held considerable weight. A race commenced to be the first to reach this unexplored Arctic terrain, driven by the aspiration for fame and fortune. The affluence of certain individuals, along with widespread public fascination, propelled the race to the North, gaining momentum in the 1900s.

Following numerous expeditions, some disastrous and others more successful, it was ultimately concluded that Atlantis did not await discovery in the realm of walruses.

In 1896, the theosophist William Scott-Elliot authored "The Story of Atlantis" (1896) to buttress the concept of root races as put forth by Helena Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophical Society. Drawing on the "astral clairvoyance" of fellow theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater, Scott-Elliot extensively elaborated on Plato's Atlantis to align with the beliefs of the Theosophical Society.

Subsequently, Atlantis became a recurring theme in Western esotericism.

Scott-Elliot crafted a series of four maps delineating four epochs: Atlantis in its Prime (below), Atlantis in its decline, Atlantis after its division into two islands—Ruta and Daitya—and his final map depicting the transformation of the Island of Ruta into Poseidonis.

By the early 20th century, the Atlantis myth had taken on a life of its own. It belonged to anyone and everyone.

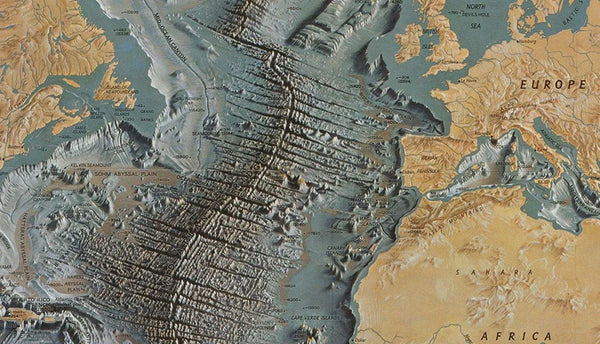

However, advancements in technology eventually afforded us the ability to examine the seafloor. Geophysical and deep ocean surveys of the Atlantic Ocean conclusively demonstrated that there is no possibility of a sunken island in that area.

An Atlantis called Thera?

There exists a belief among some archaeologists that Thera might have been the inspiration for Plato's Atlantis. Thera, now known as Santorini, a small Greek island in the Aegean Sea, met its end during the Minoan volcanic eruption around 1600 BCE.

The unearthing of Akrotiri on Thera, a city akin to Pompeii, entombed and preserved beneath layers of volcanic ash, has bolstered this hypothesis. It came to light that the Minoan Civilization was affluent, influential, and possibly displayed martial characteristics, aligning with Plato's depiction of the Atlanteans.

However, it's worth noting that the geographical location of Thera does not align with Plato's account of where Atlantis was purported to be situated: in proximity to the Pillars of Hercules, which traditionally denote the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar.

Fresco dated 1550 BCE representing ships passing Akrotiri, a Minoan settlement on Thera. It also depicts a lush and diverse flora and fauna consistent with Plato's description of Atlantis in Critias.

So, is Atlantis merely a myth? Perhaps it's a vision of what Plato's ideal society would resemble—a morality tale, one of Plato's 'noble lies,' as expounded in his Republic.

Atlantis might have been conceived by Plato as a means to educate and caution democracies against the avarice that propels military expansion. Plato understood that only a few possess the capacity, or inclination, for philosophical discourse, whereas everyone is captivated by a compelling narrative.

Yes, Plato's Atlantis was... but "its inventor caused it to disappear."

Catherine x

- Sources:

- Timaeus, Plato

- Critias, Plato

- The genre of the Atlantis Story, Christopher Gill.

- Essais sur les isles fortunées, Bory de St Vincent.

- Aristotle and Plato's Atlantis, Thorwald C, Franke.

- Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, Ignatius L. Donnelly.

- The Phantom Atlas, Edward Brooke-Hitching.

- Lost Continents, L. Sprague De Camp.

- A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, ‘Germanus

- Incredibilis’, John Edward Fletcher.

- Archaeologychannel.org

- Wikimedia & Wikipedia.